Flashblocks are all about speed – 200ms block confirmations that are streamed across the nodes in the network. Flashblocks is a streaming block construction layer for rollups that breaks each block into smaller pieces (called Flashblocks) and shares them at 200ms intervals, rather than waiting for the whole block to be built. The result is near-instant user confirmations, more efficient MEV and potentially even higher overall throughput. Before diving into the details of the peer-to-peer (P2P) propagation layer being developed for World Chain, let's take a deeper look at Flashblocks – and why they're so promising in the layer 2 ecosystem.

Flashblocks in a Flash

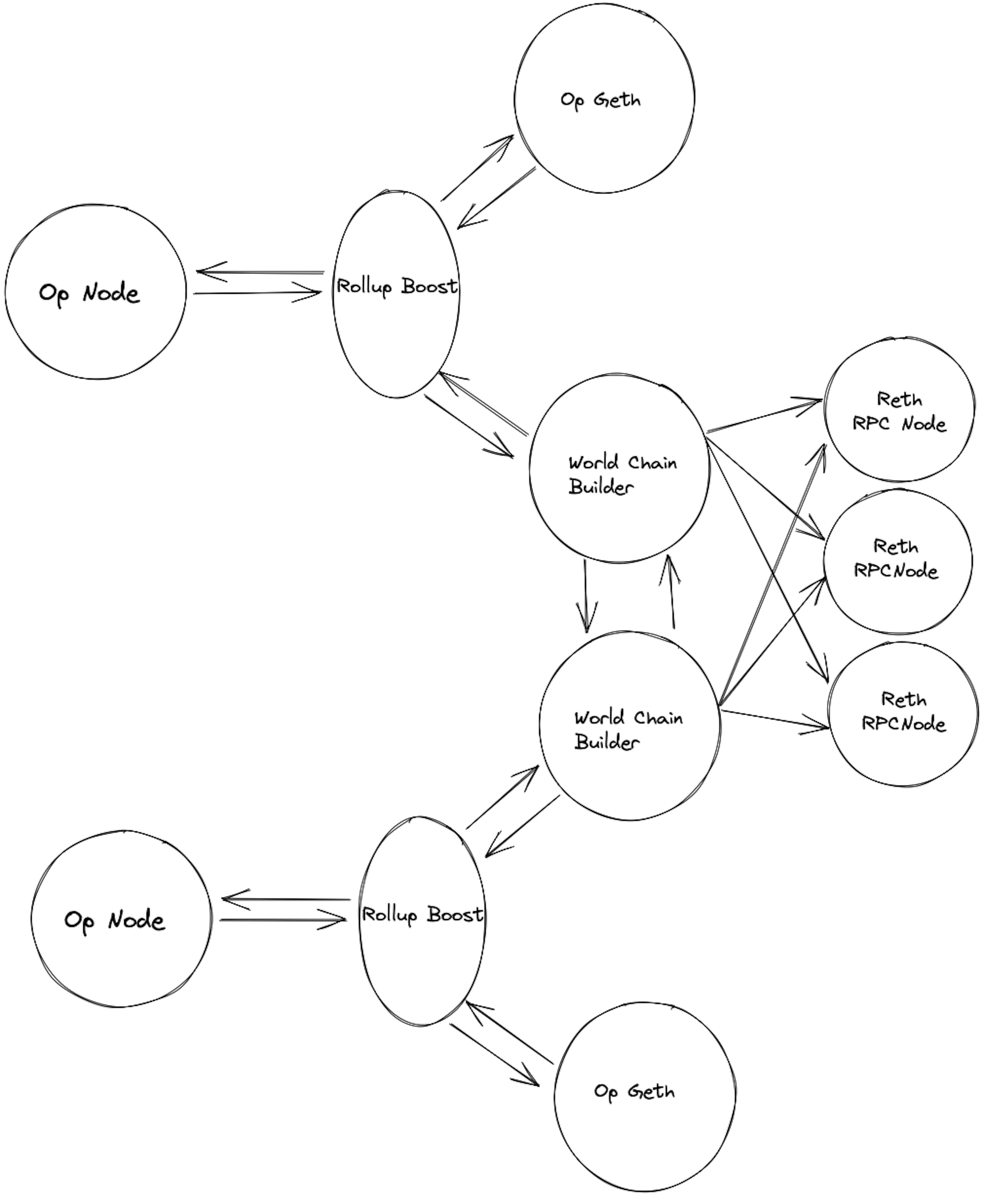

Flashblocks were introduced as an extension of Flashbots' Rollup Boost, aiming to turbo-charge OP Stack based chains (e.g. World Chain or Coinbase’s Base network) with Solana-like speed and OP Stack modularity. For those who are unfamiliar with Rollup Boost, it’s basically an extension for the OP Stack that unlocks the use of custom block builders, like those used in World’s recent release of Priority Blockspace for Humans.

While the sequencer still produces a full block every two seconds, Flashblocks split each block interval into multiple partial blocks. For example, a 2-second block might be divided into 10 Flashblocks of 200ms each. These partial blocks contain sets of transactions that are executed and streamed out continuously:

- Near-Instant UX: Users don’t have to wait a full block time to know if their transaction will make it – they receive an early execution confirmation on the next 200ms Flashblock.

- Higher Throughput: By overlapping execution and networking (and amortizing the expensive state root computation over several chunks), Flashblocks can squeeze in more gas per second overall.

To visualize this, imagine the block builder as an assembly line that doesn’t stop: transactions flow into the builder, which orders and executes them in 200ms batches, spitting out partial block segments one after another. These segments (Flashblocks) are then shipped off to RPC providers continuously. The final block (every 2s or so) is essentially the combination of the last few Flashblocks, but by then everyone’s already seen the pieces.

Now that we’re clear on what Flashblocks achieve, let’s talk about the core component that enables all this speed in a distributed setting: the Flashblocks P2P network. High-speed block streaming could easily devolve into chaos (imagine multiple chefs rapidly throwing ingredients into a soup). The P2P mechanism is the coordination layer ensuring all participants know who the head chef is at any moment and that every partial block arrives intact, in order, and verified.

The Flashblocks P2P Network: Gossip at Lightspeed

The Flashblocks P2P network is essentially a set of peers (block builders and Flashblock consumers) engaged in rapid-fire distribution of partial blocks. Unlike a typical P2P network that floods transactions from any node, this is a more tightly controlled protocol where only authorized block-building nodes can generate new messages. The goals of the Flashblocks P2P layer are straightforward yet ambitious: propagate partial blocks in near real time, coordinate which node is currently building, and do it all without conflicts between participants.

Signed, Sealed, Delivered: Authorized Messages

First, every message sent in this P2P network is signed and authorized. When a builder node creates a new Flashblock or a coordination signal, it wraps it in an Authorized envelope that includes cryptographic signatures from both the authorizer (Rollup Boost) and the builder, a timestamp, and the payload id.

Rust

This ensures a few things:

- Authenticity: Only known and authorized builders can produce messages. If a rogue node tries to inject a fake partial block, the other peers will drop it because the signature won’t verify against an authorized builder’s public key.

- Integrity: The content (whether it’s a piece of block or a control message) can’t be tampered with in transit. If altered, signature verification fails.

- Freshness: The timestamp and payload ID are used to prevent replay attacks or the use of old data. If an old message from a past block turns up, peers will recognize it as stale and ignore it.

When a message arrives, the receiving peer decodes it and calls Authorized::verify(...) using a known authorizer verifying key (a network-wide verifier) to confirm the signature is valid. Only then will it process the message. If verification fails – maybe the message is bogus or the peer is trying something questionable – it doesn’t just get ignored; the peer’s reputation degrades (the protocol has a reputation system to penalize misbehavior). If a peer misbehaves too much, it may be dropped.

A subtle detail: a node compares the incoming message’s builder ID with its own builder key. Why? To detect the scenario where it might be hearing its own message echoed back by a peer. If a node sees its own signature coming from someone else, it will log a warning – an indication that the peer is recycling data it received from another peer. That peer gets flagged for a bad message. This prevents feedback loops and the network equivalent of talking to yourself in a cave of echoes.

Flashblocks Payload Broadcast: Sharing the Goods

Once a partial block is authenticated and accepted, it needs to spread to all other connected peers as soon as possible. The Flashblocks P2P protocol implements a broadcast mechanism for this. Think of it like a relay race: one peer gets a new Flashblock chunk and immediately passes it along to others, who in turn pass it to others, and so on, almost simultaneously. Each FlashblocksConnection (representing a connection to one peer) has a stream of outgoing messages (peer_rx) that are broadcast from a central hub. When one connection receives a new Flashblock, it puts the serialized message into this broadcast stream. All other connections are listening on that stream, and each will pick up the message and send it out to their respective peer.

However, there's an important rule: don’t send the message back to where it came from. In practice, the implementation tracks the latest payload ID for each connection (an identifier for the current block being built) and which indices of Flashblocks it has seen from that peer. If a new message arrives on the broadcast channel for a connection and either the payload ID is different (meaning the message is for a new block than the one that peer last sent us) or the specific chunk index wasn’t seen from that peer, then it’s appropriate to send. If it’s a duplicate of something that peer already sent, it’s not sent again.

Duplicate Detection and Spam Control

In such a high-frequency environment, it’s crucial to be vigilant about duplicates – intentional or not. Each connection keeps a received bitmap indexed by Flashblock number, to mark which chunk indices from the current block it has gotten from that peer. If a peer sends the same chunk twice (say, chunk #1 of the current block, again), it is considered a mild offense (reputation tagged as AlreadySeenTransaction, indicating spammy or redundant behavior). One duplicate won’t get you kicked out, but it’s definitely noted – this prevents a peer from flooding the network with repeated data to try and slow us down.

Who’s cooking? Coordinating with Start/Stop Signals

One of the most challenging parts of Flashblocks P2P is coordinating who is currently publishing Flashblocks at any given time, specifically when there are multiple block builders (high availability Sequencer setups). You can imagine that normally there’s one active builder creating the Flashblocks, but what if that node goes down and another needs to take over? There must be a way for nodes to politely agree on who’s in charge of block production. Enter the Control Messages – these are the signals used to negotiate the role of “active publisher” among peers.

Rust

- StartPublish: Picture a peer waving a flag and shouting “I’m going to start building the next block now!” A node sends an Authorized(StartPublish) message to indicate it intends to become the block producer for the upcoming block (or current one, if a failover is happening). This message, like the Flashblocks, is signed and timestamped (so you can’t maliciously replay an old “I will build” from last year and confuse everyone). When others receive a valid StartPublish, they update their records of active publishers.

- StopPublish: This is the counterpart signal: “I’m stopping (or finished) my block building.” It indicates the peer is stepping down as an active builder. In practice, a StopPublish is only sent in response to receiving a StartPublish message.

StartPublish: Yielding to a New Builder

If a node is not currently building a block, receiving a StartPublish from peer X is straightforward – simply add X to the list of active_publishers. If X was already on the list, update their timestamp (they’re still active but refreshing their intent at this moment).

If a node is currently building when a StartPublish comes in from someone else, that’s a potential conflict. The implementation’s strategy here is somewhat selfless (and pragmatic): The builder stops publishing to avoid a tug-of-war. Upon seeing a peer’s StartPublish message while the builder is in a Publishing state, it creates a StopPublish message signed using its most recent authorization. This essentially relegates a node’s role as the publisher. Its status switches to NotPublishing, and the other peer is listed as an active publisher.

If the builder was in a WaitingToPublish state and it receives a StartPublish from another peer, it chooses to ignore the request in terms of overriding anything. In practice, simultaneous StartPublish signals might happen in a double failover scenario (two nodes racing to replace a failed builder). It’s acknowledged that this race could happen (“double failover” scenario) but there is no need to immediately resolve it. Instead the protocol relies on the underlying RAFT consensus algorithm which selects the sequencer leader (and thus Flashblocks publisher) to eventually regain consistency.

StopPublish: Stepping Aside Gracefully

When a StopPublish message comes in, it means a peer who was an active builder is now out. How it’s handled depends on the builder’s current state.

If the builder wasn’t publishing (just a passive observer or waiting), it simply removes that peer from the active_publishers list. “Got it, peer Y is no longer building.” If Y wasn’t in the list (which would be odd, like getting a goodbye from someone who it didn’t know was building), a warning is logged about an unknown publisher.

The interesting case is if the builder were waiting to publish (meaning it wants to build the next block). If it then receives a StopPublish from a peer, that means the current builder has finished. This is used as a trigger to take over and remove that builder from the active list. Then the builder checks: is the active publishers list now empty? If yes, that means no one else is currently building – the builder can transition its state to Publishing. This implies it will begin building the new block (it had an authorization to do so already, which it now can utilize) or continue building atop the previous publisher’s work (more on this later). If the active list isn’t empty (perhaps another backup builder is still in line or started), it will remain in waiting. Essentially, only when the last other active builder steps aside does the new builder step up to publish.

Failover safety: if one builder crashes or exits, another can take over immediately, even within the same block, so the chain keeps running at 200ms pace without missing a beat. All of this is done without a central coordinator – it’s purely through P2P signals and local decisions based on those signals, which is important from a decentralization perspective. It’s like a group of chefs in a kitchen seamlessly taking turns: if the head chef drops the pan, the next chef in line grabs it and continues cooking the meal, while the rest of the kitchen is instantly aware of the swap.

Incremental Execution and the Need for Speed

On receiving and validating each Flashblock, the node will immediately execute it against its local state, serve RPC requests, and optimistically compute the state root. By the time the final block is assembled, the node has already done most of the work. Continuous execution is one of the big value propositions of Flashblocks: instead of a huge pause-and-process at each block boundary, you process transactions continuously, staying in sync with the head of the chain.

Reputation and Resilience

Before we wrap up, it’s worth noting the P2P protocol isn’t naive about adversarial conditions. It has a built-in notion of peer reputation (as mentioned earlier). Misbehaviors like sending invalid data, outdated messages, or obvious spam will impact reputation. This could eventually lead to disconnecting a bad peer. The implementation uses ReputationChangeKind::BadMessage for serious offenses (invalid signature, replaying messages back, etc.) and lighter flags like AlreadySeenTransaction for duplicates. The idea is to keep the participants small and honest – only authorized builders or well-behaved nodes get to stay in this high-speed gossip network.

Final Thoughts

P2P Flashblocks propagation is a fascinating blend of high-performance networking and consensus coordination. It’s not common to see block building occur 5 times a second in perfect harmony. By carefully coordinating who builds and when (using Start/Stop signals) and rapidly broadcasting partial block data, Flashblocks achieve a kind of concurrency between block production and block propagation without collapsing into confusion.

For developers, the key takeaways from the P2P mechanism include the importance of robust message validation (signatures and timestamps), efficient broadcast (to not become a bottleneck at high frequency), and state management for incoming data (tracking indices, payload IDs to know what’s what). It’s a brave new world where OP Stack L2s might routinely have sub-second (or even sub-quarter-second!) confirmation times.

As is typical with World and Flashbots initiatives, Flashblocks is pushing the boundaries of what’s possible by rethinking the roles of time and communication in block building. It borrows conceptually from Solana (fast block propagation) and brings it into the OP Stack. The result is a high-wire act of engineering that’s as cool as it is profound – a network of nodes flawlessly coordinating at breakneck speed, all so your transactions land in 200ms. Not quite time-travel, but in the blockchain world, it sure feels close!

Footnotes

📚 Source Code: This post discusses the implementation details of Rollup Boost PR #373. Check out the link for the latest code and documentation.

Mga kaugnay na artikulo

Remainder: World's GKR prover for ML and more

Today we announce the open-sourcing of Remainder (Reasonable Machine Learning Doubly-Efficient Prover), Tools for Humanity's in-house GKR + Hyrax proof system. Remainder enables World's users to run ML models locally over private data and prove that they executed them correctly.

Introducing World ID 4.0 - Request for Comments

The new World ID 4.0 upgrade introduces account abstraction with multi-key support, transforming a World ID from a single secret into an abstract record in a public registry. This increases protocol resilience by allowing the introduction of multiple key support, portability, recovery and improved privacy.